Ruminathans are pretty rare. I publish one about every two months on average, with high variance. I could probably increase my output substantially if I used generative AI (gAI) to the fullest. The reasons I don’t are:

- The output of gAI is persistently not up to my quality standards.

- I want to exercise my writing and thinking ability, so outsourcing that work to gAI would be like asking a robot to go jogging on my behalf.

- I genuinely enjoy writing and thinking, so outsourcing that work to gAI would be like asking a robot to make love on my behalf.

That said, here are some ways I use gAI in the writing process: What it does and doesn’t do for me, and what I think that reveals about the future of essay-writing as a human endeavor.

Research

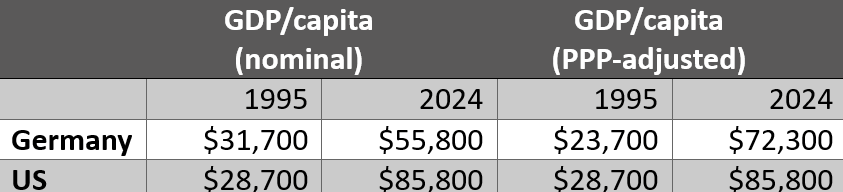

As the quality of traditional search declines in the face of the SEO arms race and the explosion of (gAI-produced) slop, it’s easier to find empirical data by posing research questions in ChatGPT (I’m using a paid version). In my recent posts about macroeconomics it helped me find the right databases. You have to verify that the links exist, that they are reputable, and that they say what ChatGPT says they say.

It’s far too easy, though, to use this “research” to cherry-pick data. You can ask ChatGPT to “Find data that supports [INSERT PET THESIS HERE]!” and it will oblige. It won’t push back and warn you that the balance of the evidence undermines your pet thesis.

You can, of course, prompt it to evaluate the available data. But that reveals the limitation: You can prompt it to produce anything you want. Asking it to evaluate the available data implies that you are looking for a balanced assessment. It will oblige, leaving you wondering if it just mirrors the biases embedded in your own word choice.

An easily confused sparring partner

Exploring a single topic in a longer conversation with ChatGPT requires a lot of care. The fact that it does not get meaning becomes apparent when you whiplash it around. Ask it to defend a thesis, then defend the antithesis, and then ask it to revert to arguing the original thesis: After that back and forth, it tends to get very muddled about which argument supports which position. It neither notices inconsistency nor is it embarrassed by it.

Say what you will about humans and their ornery unwillingness to update their priors: You can count on them to stick to their guns, and that’s what makes a good sparring partner.

ChatGPT is not a real sparring partner: Dance around it for a minute or two, and it will start punching itself in its tattooed-grin face.

Flattery will get you everywhere

Speaking of its ever-chipper attitude: Once I write a finished draft of an essay, I ask ChatGPT to evaluate it for clarity, elegance, and originality. Even 5.0, which is supposed to have overcome the obsequiousness of prior versions, is still an inveterate flatterer. And hey, it’s nice to hear some positive feedback.

To its credit, if I push a half-written fragment through, it identifies that it’s flawed and provides some feedback about how to improve it. But its concrete suggestions are largely unusable: It will never sit you down and say: “I don’t understand your point” or “This is too clunky to be salvageable” or “Stop beating this dead horse.” And that’s feedback that you need to hear sometimes.

Bottom-line: This step adds very little value to the writing process. I still do it because, yes, the charitable feedback provides a little pick-me-up after I’ve reached a draft. And I’m still hoping that someday it sounds a big alarm… but I’m not holding my breath.

My sworn enemy

You can, of course, prompt it to take a critical view. My preferred approach is to ask it to write a 300-word review of the article from the perspective of the author’s sworn foe.

The result is a cold slap in the face. There’s little of substance in the critique: usually it does not identify anything – neither stylistic nor content-related – that I did not anticipate and consciously choose. I find this step helpful, though, insofar as it shows me how someone might react emotionally.

To some extent, I can anticipate the perspective. There are people who are, shall we say, uncharitably disposed towards me. I can – equally uncharitably – simulate their voices in my head without ChatGPT’s help. But after the initial flattery, my bot-enemy’s perspective is a salutary palette-cleanser.

After my foe has weighed in, I usually ask ChatGPT which of his critiques are fair. If I agree and can make some changes without too much effort, I do so, but usually not the changes ChatGPT suggests.

The “best available editor”

Ethan Mollick, one of gAI’s biggest boosters, introduced the concept of the “best available human” to argue in favor of widespread use of gAI. “Sure,” says Mollick, “the most skilled humans can still do many tasks better than AI. But the issue is not what the most skilled humans can do but what the best available human can do. And much of the time, the skilled humans aren’t available.”

Frankly, I’ve been underwhelmed by Mollick’s writing. In this case it seems like he’s unfamiliar with the concept of negative numbers and the value “zero” as a valid solution to many problems. If the best available human would do a billion dollars of damage, and an AI agent only does a million, the correct choice is to abandon whatever the f#*k you’re doing, not outsource the problem to AI.

Still, in Mollick’s spirit: I’ve tried to prompt ChatGPT to be an editor at a national magazine who is willing to read my article and ask guiding questions and then give me a thumbs up or down for publishing it. An actual national-league editor is not available, but her simulacrum is.

The editor succeeds at asking a set of interesting questions, and it can be prompted to stop asking and reach a verdict. As interesting as some of the questions are, the problem remains: It will not shoot me down. And sometimes, an idea has to be shot down.

Helpful, question-led suggestions – while perhaps leading to incremental improvements – serve only to lead me further down a rabbit-hole, when what I really need to do is cut my losses and move on to the next idea.

The value of blind spots

We all have our blind spots. They come naturally from being an embodied soul with a particular life history. What we think and what we write is just as much a product of what we don’t see as what we do see.

That’s what makes conversation so compelling – and reading and writing is a form of conversation. Through others’ eyes we can peer into our own blind spots. But it’s necessarily their own constrained perspectives that give them that vantage point. An outsider’s perspective is not valuable only for the unfamiliar ideas she brings; it’s equally valuable – sometimes more valuable – for being unburdened by the ideas the insiders take for granted.

In a good conversation – including one with an editor – your partner will point out your blind spots unprompted. I’ve not seen ChatGPT do this. I’ve tried. This essay went through the process I described above, intentionally without this section on blind spots, which I had mentally sketched out but not committed to pixels. The idea of “blind spots” lay in the incomplete essay’s blind spot. ChatGPT did not point it out (nor did it point out any other noteworthy blind spots).

You can, of course, prompt the bot to look for blind spots. An explicit prompt (“Look for blind spots”) does not work: You get no fresh insights. You can ask it to write a comment from a particular writer’s perspective (“Imagine you’re George Orwell”) and it does better, but mostly it delivers a superficial emulation of the style, not a fresh perspective. It’s nowhere near the experience of being confronted with someone who makes completely different assumptions from your own.

Large language models seem to encompass every perspective, and the perspective from everywhere is a perspective from nowhere.

I could easily use gAI to create more output, more quickly. But I struggle to see what service I’d be doing others or myself.